Anterior Knee Pain Relief in Nebraska

Anterior knee pain, often experienced as discomfort on the front side of the knee behind the kneecap, is a common issue that can affect daily activities and athletic performance. At Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute, P.C., we offer comprehensive pain relief for anterior knee pain through our specialized knee pain treatment services.

Our team of experienced professionals is dedicated to diagnosing the underlying causes of your knee pain and providing personalized treatment plans to alleviate discomfort and restore mobility. Discover effective solutions for anterior knee pain at Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute, P.C., where your well-being is our priority.

What Is Anterior Knee Pain?

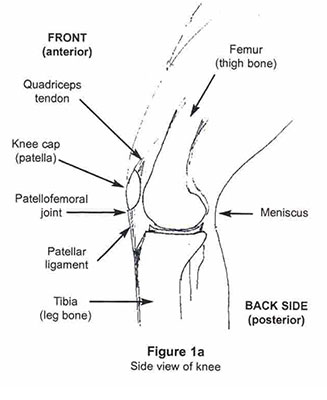

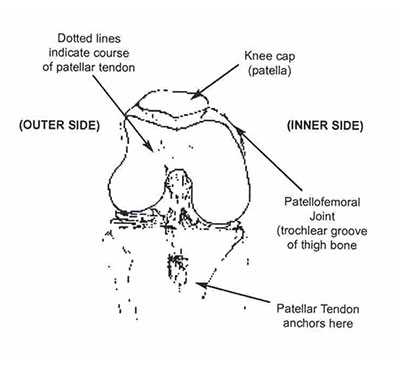

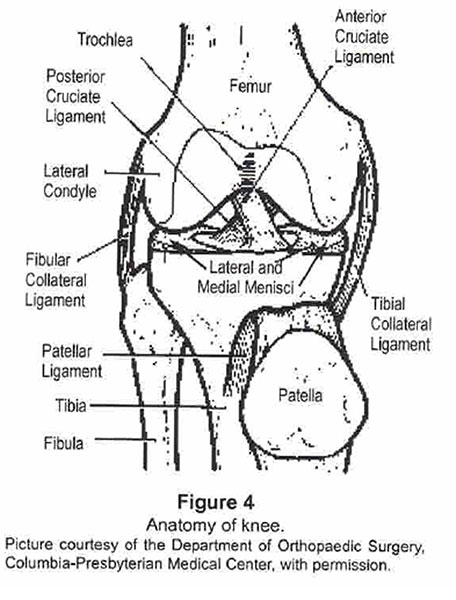

Anterior and posterior are anatomic terms for front and back. Anterior knee pain almost always results from irritation of the undersurface of the kneecap (patella) and the underlying trochlear groove of the femur (thigh bone). (Figure 1a & b).

Figure 1b

Bent knee as viewed from the front.

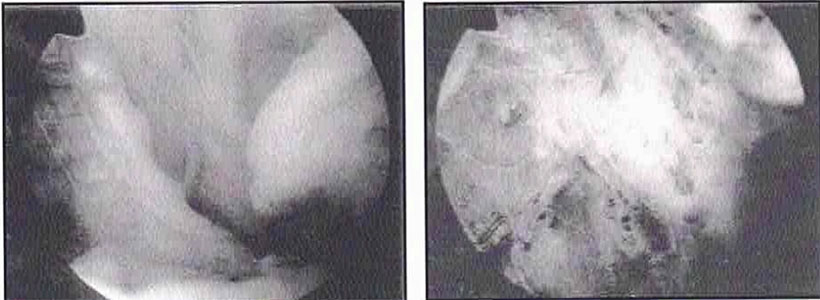

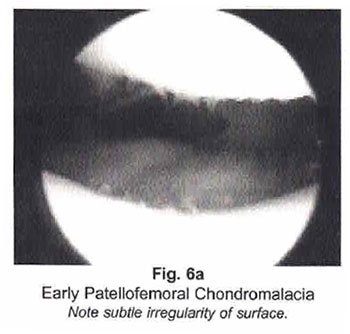

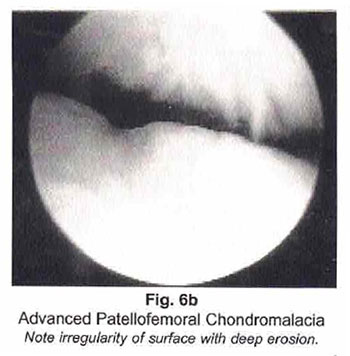

An abnormally shallow trochlear groove or high or low-riding kneecap may also predispose to anterior knee pain. In some people, the pain is a result of arthritis, in others, it is due to poor joint mechanics related to inadequate muscle or the unusual shape of the kneecap. In advanced cases of arthritis behind the kneecap, grinding or popping open are complained of due to irregular or roughened cartilage surface. This usually has been termed patellofemoral chondromalacia which literally means "sick cartilage." (Figure 2)

Figure 2

Early patellofemoral chondromalacia (irregularity of surface).

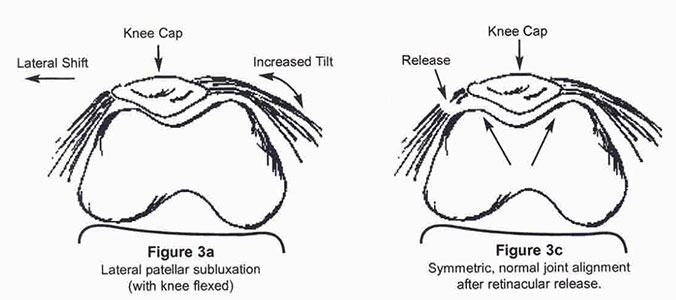

Sunrise x-ray view of patellofemoral joint depiction with patellar subluxation (Figure 3a and 3b) and realignment after surgical correction (Figure 3c). (lateral retinacular release)

Symptoms of Anterior Knee Pain

Symptoms usually include some or all of the following: increased discomfort climbing stairs, difficulty kneeling and squatting, a grating sensation with knee motion, a feeling that the knee is going to give out, and swelling. In fact, this is the most common reason for the complaint of knee instability.*

Women teenage or older experience this problem much more frequently than men. This is probably related to the greater angulation (valgus) in a woman's knee after the age of puberty, when the pelvis becomes wider and the knees remain centered toward the midline, giving many women the appearance of ''knocked knees." Additionally, most women have greater ligamentous laxity and less muscle tone than men. Often a combination of outward migration and abnormal tilting of the kneecap are treatable causes of the symptoms (Figure 3a, 3b, & 3c). This is called patellar subluxation.

Occasionally, anterior knee pain is a result of inflammation in the bursa directly in front of the kneecap. When this occurs there is usually an infection associated with swelling and redness. It can also appear this way with gout.

Figure 3b

Lateral Patellar Subluxation with early arthritis.

Plica Syndrome

A very rare cause of anterior knee pain is plica syndrome (3d & 3e). This is a scenario wherein a thickened, abnormally large fold of the inner lining of the knee (synovium) begins rubbing on the front of the femoral condyle (one of the cartilage-covered ends of the thigh bone).

Figure 3d, left, and Figure 3e, right

Figure 3d: Plica

Figure 3e: After Plica Excised

Anatomy

The anatomy of the knee is very simple. The front of the knee is comprised of the kneecap or patella, which is suspended with the patellar ligament below, extending to the upper surface of the Leg bone (tibia), and the quadriceps tendon above coming from the quadriceps muscle. The kneecap rides in a cartilage-lined trough on the end of the thigh bone (femur) called the trochlear groove.

Because the knee does not move simply as a hinge, the kneecap tends to slide outwardly at some point in the arc of knee flexion. This results in subtle, visible, and in some people, audible clunking. Normally, this is not painful. The kneecap is stabilized by patella femoral ligaments (bands of soft tissue on either side of the end of the thigh bone) in addition to the quadriceps and patellar tendons and the medial or lateral retinacula. (Figure 3a & 3c above)

Diagnosis

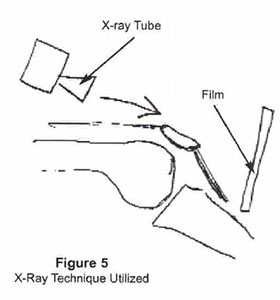

Diagnosis requires a careful physical exam, sunrise x-rays (Figure 5), and a review of complaints.

Non-surgical Treatment of Anterior Knee Pain

Non-surgical treatment for pain behind the kneecap, specifically patellofemoral irritation, often includes a combination of specific exercises, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID), and using a neoprene stabilizing sleeve. Avoiding activities like kneeling and repetitive squatting can also help relieve symptoms. In persistent cases, a "cortisone" injection may be administered into the joint to reduce inflammation. Additionally, if a person is overweight, weight loss is crucial to decrease the stress on the kneecap, similar to reducing pressure on sandpaper to prevent surface abrasion.

Medication

According to Finestone et al., 80% of adults with anterior knee pain experienced relief without any specific treatment. In comparison, Fulkerson and Folcik reported that anti-inflammatory medication alleviated pain in 60% of patients within 5 days.

Exercise

Extensive research in rehabilitation centers has focused on identifying the most effective physical activities for individuals experiencing anterior knee pain. Recently, the debate has centered around closed versus open chain strengthening exercises. Evidence suggests that a combination of these exercises in physical therapy can best relieve pain.

Consulting directly with a physical therapist is more beneficial than simply reading about these exercises. The duration of nonoperative treatment typically depends on the severity of symptoms and progress, with a minimum of six months of conservative management often recommended.

Surgery for Anterior Knee Pain

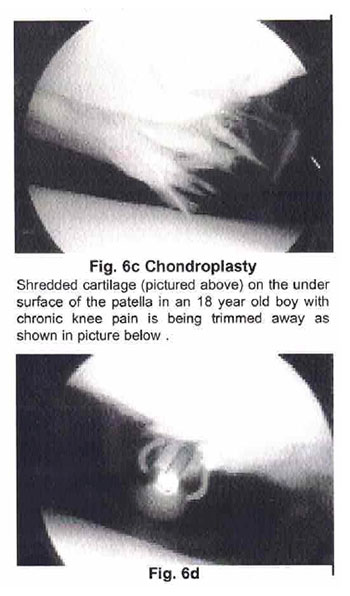

At Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute, P.C., we offer specialized surgical solutions for anterior knee pain, particularly when nonoperative treatments like medications, exercises, and braces have not provided adequate relief. Our arthroscopic surgery is a minimally invasive outpatient procedure performed through small puncture wounds on the knee, utilizing advanced fiberoptic visualization to examine and treat the inside of the knee.

In cases where pain is caused by the malalignment of the kneecap, we may perform a lateral retinaculum release to shift the kneecap and alleviate pain through local denervation, without affecting skin sensitivity. For more complex cases, we may adjust the pull direction of the ligaments on the kneecap by relocating the patellar tendon to improve alignment and function.

For patients experiencing severe arthritis behind the kneecap, often due to trauma, we may consider a patellectomy or, in specific cases, a patellofemoral joint replacement. This involves the insertion of a metal and plastic gliding surface to restore function. However, this option is typically recommended for older, less active individuals due to the potential for implant loosening over time. For those eligible, a total joint replacement may be suggested to provide comprehensive relief and improved mobility.

Our team at Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute, P.C. is dedicated to delivering effective, tailored surgical solutions for anterior knee pain, enhancing your quality of life.

Complications of Surgery

The reported rate for infection of arthroscopic surgery varies from a high of 1 in 500 to a low of 1 in 2000 people. Of people who undergo lateral retinacular release, the most chronic knee pain is being trimmed away as common surgery for anterior knee pain, 7% develop painful swelling of the knee due to immediate postoperative bleeding. This can usually be prevented by wearing a compressive wrap for a few days after the operation.

The person may have a visible tender scar that persists after surgery and it is possible, though unlikely, that the surgery will have no effect on the preoperative pain and surgery could even worsen a person's complaints. Clotting of veins in a patient's case (phlebitis) rarely occurs.

Recovery from Surgery

Recovery depends upon the type of operation performed. Generally, a couple of days after surgery the person spends their time lying around with an ice pack on the knee doing every exercise. Over the next few weeks, they progress to relatively normal mobility.

Usually, we will let patients walk on the leg immediately. Return to participation in sports depends on the operation performed, generally about six weeks. It generally takes six months or more, however, to reach maximum medical improvement after reconstructive knee surgery. The main benefit is usually achieved within 3 to 4 months

Surgical Outcome

Surgical Treatment: (Performed only on patients who failed nonoperative treatment.)

Lateral release: 77-88% good to excellent results (JBJS 1997).

*Other causes of knee instability symptoms are torn cruciate ligament, unstable torn meniscus, or a loose body within the knee.

**Open chain exercises are those that are performed without machinery or any direct resistance such as straight leg raising. Closed chain exercises are those that are done with contact with the floor such as squatting, leg presses. etc.

***e.g. Fulkerson osteotomy