Impingement Syndrome Treatment in Nebraska

Are you struggling with shoulder pain? This could be the result of impingement syndrome, which often presents with symptoms such as weakness, difficulty in lifting objects, and discomfort when lying down. To ensure you receive the correct treatment for long-term relief, obtaining an accurate diagnosis is crucial.

At Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute P.C., our specialty is diagnosing and effectively treating shoulder pain. We provide comprehensive orthopaedic care, including advanced impingement syndrome treatment and surgery in Nebraska. Our goal is to help you stop enduring shoulder pain and start enjoying life once again.

Don't let shoulder pain restrict your life. Schedule an appointment with us today for expert orthopaedic assistance. With our personalized impingement syndrome treatment, we can help you rediscover the joy of a pain-free life.

Understanding Impingement Syndrome

Shoulder pain is one of the most common reasons individuals consult an orthopedist. Aside from recurrent dislocation, most shoulder issues tend to arise after the age of 30. It is crucial to distinguish pain originating from the shoulder itself from pain that may be referred from other sources, such as degenerative intervertebral discs in the neck, heart attacks, or carpal tunnel syndrome.

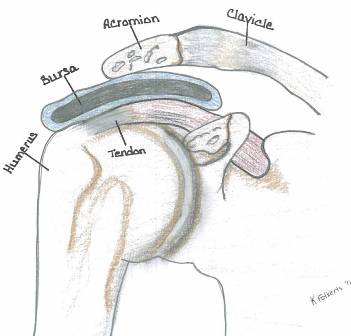

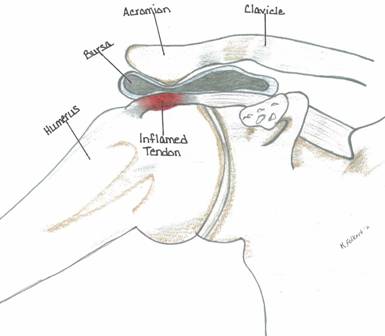

Impingement syndrome specifically refers to pain caused by the rubbing of the rotator cuff tendon and/or biceps tendon against the overlying acromion.

Normal Acromion

Prominent Acromion

Normal Acromion (Type 1)

Prominent Type 3 Acromion

Impingement Process and Acromion Types

An impingement process tends to occur in several ways:

A very prominent acromion; typically it is a type 2 or type 3. People with a flat type 1 acromion rarely see an orthopedist for shoulder pain.

As the person ages, the acromion will often enlarge where it attached to the coracoacromial ligament. The acromion seems to follow the course of this ligament downwards, forward and towards the midline of the chest. Thus, we are more likely to see a very prominent acromion in an older individual. Arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint is very common at an early stage at age 40 and older. The majority of people are completely without symptoms (asymptomatic). As degenerative arthritis progresses the joint enlarges; this is true anywhere in the body. In the shoulder, you can feel it when you run your hand over the top of the shoulder as a lump.

The same amount of prominence projects downward and that is what can rub on the rotator cuff very close to where the tendon comes off the muscle at the edge of the glenohumeral joint. Impingement can be affected in a very small percentage of people by posture. The scapula rotates over the humeral head. If one has their shoulders “scrunched up”, pointed towards the breastbone, the acromion may well be relatively more prominent over the rotator cuff. When examining a person with this situation, the shoulder blades are really separated widely on the backside. This is referred to as scapular dyskinesia, a concept popularized by Ben Kibler, MD, of Kentucky. It is very hard to overcome this dysfunctional motion and the associated complaints that come from it. Concentrate on good posture with shoulders back and head held high.

Anatomy

The shoulder is one of the most intricate and dynamic joints in the human body. It is suspended from the chest wall by the scapula (shoulder blade) and surrounding muscles. Within the shoulder, there are two primary joints: the acromioclavicular (AC) joint and the glenohumeral joint, along with a functional pseudo joint between the shoulder blade and the chest wall. The stability of the glenohumeral joint relies on a combination of muscles.

Four key muscles make up the rotator cuff: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles not only facilitate movement of the glenohumeral joint but also play a crucial role in stabilizing it. An imbalance in these muscles and their stabilizing forces can lead to painful impingement. Furthermore, variations in normal anatomy are often the primary cause of non-injury-related shoulder pain.

Causes of Impingement Syndrome

Age-related changes in the shape and prominence of the shoulder skeleton, along with degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon (the upper portion of the rotator cuff) and variations in physical fitness, likely contribute to the majority of symptoms experienced. The onset of pain typically arises from this natural progression.

Impingement occurs when pressure is exerted against the rotator cuff, leading to pain. Impingement syndrome is closely associated with various factors, including the elongation of the acromion's anterior edge as the coracoacromial (CA) ligament undergoes calcification with age. This anatomical change may explain the increased incidence of impingement syndrome in older adults. Most individuals affected by this condition are over 30, though it can occasionally appear in teenagers.

Poor muscle tone, muscle imbalances, or muscle fatigue may cause the shoulder to shift into a position where the rotator cuff and the overlying subacromial bursa become compressed by the acromion and the CA ligament due to dynamic instability. True instability-related impingement syndrome is a challenging diagnosis, classified as a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning other potential sources of discomfort must be ruled out first. This condition is most commonly observed in throwing athletes with hypermobile joints.

Differentiating between bursitis and tendonitis can be difficult, as the bursa sits directly on top of the rotator cuff tendon. Practically speaking, treatment for one condition often addresses the other, making the distinction less significant. Given the limited space available for the rotator cuff in the subacromial area, any loss of stability due to fatigue, ligament laxity, or muscle imbalance—whether accompanied by pronounced acromial bone or not—can result in the bursa being pinched by the CA ligament and the acromion.

Symptoms of Impingement

Pain often occurs when lying down and especially with motion of the shoulder from about 60-120 degrees forward and to the side.

Weakness and difficulty lifting things due to pain.

Symptoms of AC Arthritis

Pain from 120 to 180 degrees of abduction.

Pain at the top of the shoulder.

What the Doctor Notes During the Exam

Decreased range of motion

Localized tenderness

Guarding/hesitation on active motion

Relief of pain with injection of local anesthetic

Diagnosis of Impingement Syndrome

A thorough examination, along with a comprehensive history of symptom onset, is crucial for an accurate diagnosis of impingement syndrome. X-rays play a vital role in ruling out fractures and evaluating the shape of the acromion. They are also important for detecting the presence of arthritis by assessing bone density (sclerosis), joint space narrowing, and extra bone formation (spurs or osteophytes) while excluding calcified tendon deposits.

If symptoms do not respond to medication or exercise, an arthrogram becomes necessary. This straightforward procedure involves sterilely injecting a contrast medium into the shoulder joint under local anesthesia. The goal is to determine if the contrast leaks from the normally sealed joint space.

MRI scans, while sometimes considered, are often less effective than arthrograms for this purpose, as they struggle to differentiate between inflammation of the rotator cuff tendons and tears. Additionally, MRI scans can be three times more expensive and are generally only helpful in rare cases of recurrent rotator cuff ruptures.

Unfortunately, many individuals experiencing impingement symptoms often contend with multiple concurrent degenerative processes, such as cervical arthritis or pinched nerves. This complexity makes isolating the problem and finding effective solutions challenging. Sometimes, treatment involves a process of elimination, addressing each individual issue to narrow down the cause of pain.

Treatment for Impingement Syndrome

The initial treatment for rotator cuff impingement tendonitis varies based on the severity of symptoms. For individuals experiencing moderate to severe pain and limited range of motion, a corticosteroid injection into the subacromial space is often an effective and painless method to quickly alleviate irritation—much like dousing a fire with water.

Depending on the extent of inflammation and the degree of bone prominence impinging on the tendon, multiple injections may be required over several weeks. This approach is frequently complemented by oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), resulting in effective relief for about 70% of patients.

Surgical Solution for Impingement Syndrome - Acromioplasty

If pain persists and affects your job or disrupts your sleep, it may be time to consider minimally invasive surgery after several months of unsuccessful treatment. This procedure can effectively address the issue.

Dr. Ichtertz possesses extensive expertise in performing arthroscopic shoulder surgery for patients in Nebraska. The procedure involves using a fiberoptic scope to examine the interior of the shoulder through small puncture wounds. During the surgery, any prominent bone and damaged tissues are trimmed. In approximately 40% of cases, the outer clavicle at the AC joint also requires trimming.

This approach minimizes discomfort and often allows the surgeon to proceed without imposing strict activity restrictions on the patient afterward. Recovery from the initial surgery is swift, with many patients able to return to work within a week. Typically, a period of 3 to 6 months is needed for individuals to achieve full or near-full range of motion with minimal to no residual pain.

Treatment for Torn Rotator Cuff Tendon

In the event that the rotator cuff has frayed through and ruptured, it is usually necessary to excise the damaged, degenerative portion of the tendon and reattach it to the bone. This precludes active flexion (forward elevation) and abduction (elevation away from one's side) of the shoulder for about 4-6 weeks. Heavy lifting should be avoided for up to 3 months.

Impingement Syndrome and Labral Tears

The glenoid (socket) is flat. The labrum acts as a flexible retaining wall helping to maintain the humeral head in a stable position with the glenoid. Shear stresses and age probably account for most labral tears. It's difficult to tell the extent of symptoms developed from a torn labrum rather than the impingement process (acromion jams into cuff). Due to the potential pain contribution, labral tears were usually trimmed or repaired by an anchor to eliminate this source of pain. Impingement is relieved with acromioplasty at the same time.

Labral tears are fairly rare overall. The results of repair of the labral tear are unpredictable. Most agree that repairing them in persons older than about 40 years old is prognostically bad with the people ending up with a lot of stiffness. Dr. Ichtertz believes the trend now is to cut the biceps tendon just off of the labrum and secure it to the upper end of the humerus bone, i.e. biceps tenodesis. By doing this the biceps tendon is no longer pulling on the labrum. It has been reported by Paschal Boileau, MD, a well-respected shoulder surgeon, that he has done this in a large series of patients including Olympic competitors without treating the labrum, just the biceps, and the patients did fine.

Biceps tenotomy, an alternative to biceps tenodesis, has a tendency to result in some residual weakness, perhaps 10-20%, but somewhere between 20-40% of the people undergoing this procedure will continue to have some aching in the shoulder in addition to a deformity from the shortened muscle (Popeye muscle). Tenotomy is much easier than tenodesis for the surgeon, but one has to weigh the odds. Dr. Ichtertz is in favor of biceps tenodesis in the appropriate patient. Rarely would he recommend a tenotomy based upon the relative ease over tenodesis and the potential side effects of tenotomy.

The ideal patient for a biceps tenotomy according to Paschal Boileau, MD, is a patient with a non-repairable rotator cuff tear who maintains good mobility. The worst indication for a biceps tenotomy would be someone with pseudoparalysis of the shoulder with a near irrepairable rotator cuff tear.

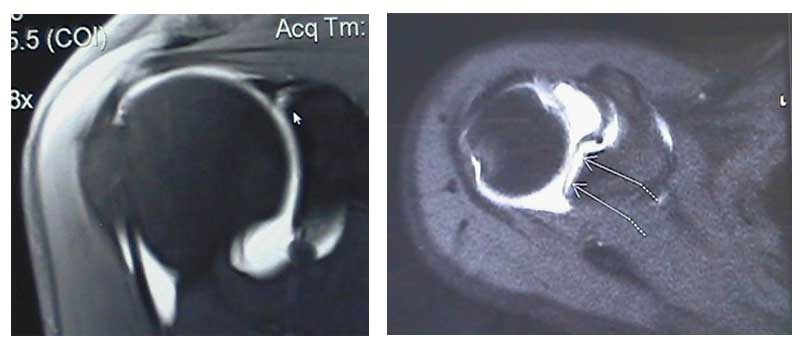

Above are MRI images of labral tears. The arrows in each image are pointing to where the dye has leaked into the labral tear.

WARNING: MAY CONTAIN GRAPHIC IMAGES

Preventing Frozen Shoulder

While undergoing treatment with medication, it is important to make sure that you maintain as much motion as possible to prevent a frozen shoulder (aka adhesive capsulitis). This is a painful situation wherein the capsule of the shoulder tightens up, restricting motion.

In order to maintain motion, it may be necessary to have you seen by a physical therapist for gentle passive and active assisted range of motion in association with application of hot packs and/or ice. The exercise can also be done at home but it's sometimes hard to get family members to get involved in painful situations. Severe contracture requires stretching the shoulder under general anesthesia, so don't let it occur in the first place!

Calcific Tendonitis

If a person presents with calcific tendonitis, cortizone injection usually rapidly resolves the problem. It is recommended that the medication be injected directly into the rotator cuff in the area of the calcification (supraspinatus tendon).

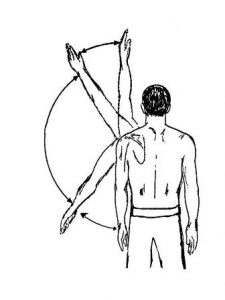

While recuperating, frequent overhead reaching, grasping, throwing and circumduction motion such as washing a car, etc. are discouraged because of their exacerbating effect on the impingement process. This diagnosis almost always excludes a torn rotator cuff.

Post-Op Synopsis for Impingement (Rotator Cuff Intact)

- On 3rd post-op day return to work as tolerated

- Physical therapy if full motion has not been obtained within 2-3 weeks of surgery

- Anticipate maximum medical improvement 3-6 months after surgery

Sports and Impingement Syndrome

The general principle of being released back to sports is it’s best to resume the game slowly and progressively. A range of motion exercises should precede your game. Limit play time initially, then slowly increase the intensity and duration of your game. In some sports, i.e., tennis, overhead swinging may be avoided.

Swimming: Breast or side stroke may come more easily than front crawl or butterfly strokes. Backstroke may be well tolerated. Consider alternating your swimming style.

Throwing Sports: Start with easy throwing, then gradually increase to harder throwing. Try to maintain a smooth throwing motion that will make use of the overall strength of your body.

Surgical Results

Results of surgical treatment depend upon age, activity level, occupation, or non-occupation causation and associated degenerative conditions such as cervical degenerative disc disease. Overall, studies have shown that about 85% of people get a very good result after treatment for impingement or a torn rotator cuff.

Time from the onset of symptoms to treatment may be important, especially for a torn rotator cuff (best if repaired within 3 weeks of tear). In some cases impingement syndrome seems to cause tearing of the rotator cuff, thus, intervention for impingement may also be preventing a torn rotator cuff.

Bigliani LH, Morrison DS, April EW: The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Ortho Transactions, 1986;10:228.

Burkhead Jr, WZ: The Biceps Tendon. (Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1990. The Shoulder, Chpt 20, pp. 791-836).

Calvert PT, et. al.: Arthrography of the shoulder after operative repair of the torn rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1986;68B 1:147-150.

Crymble, B. “Brachial Neuralgia and the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” British Journal of Medicine, Vol. 3, 470-451, 1968.

Edelson JG, Taitz C: Anatomy of the coraco-acromial arch; relation to degeneration of the acromion. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1992;74B-4:589-594.

Edelson JG: The ‘hooked’ acromion revisited. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1955;77B-2:284-287.

Gartsman G: Arthroscopic acromioplasty for lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1990;72A-2:169-180

Ha’eri G, et. al.: Shoulder impingement syndrome: results of operative release. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1982;168:128-132.

Kummel BM, Zazanis GA: Shoulder pain as a presenting complaint in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1973;92:227-230.

LaBan, Myron M., Zemenick, GA, and Meerschaert, JR. “Neck and Shoulder Pain: Presenting Symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” Michigan Medicine, September 1975, pages 449-450.

Matsen FA III, Harntz C: Subacromial impingement. (Philadelphia, PA: Saunders 1990. The Shoulder, Chpt 15, pp. 623-246).

MRI of rotator cuff tears. MR Insights (Orange, CA: Alliance Imaging, Inc.), Vol. 4, No. 3, Fall 1994.

Neer CS II: Impingement lesions. Clinical Ortho & Related Research,1983;173:70-77.

Neer CS II: Anterior acromioplasty for chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1972;54A:41.

Nirschl RP: Rotator cuff tendonitis: basic concepts of pathoetiology. AAOS Instructional Course Lect., 1989;38:439-445.

Post M, Cohen J: Imipingement syndrome: a review of late stage II and early stage III lesions. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1986;207:126-132.

Rathbun JB, Macnab I: The microvascular pattern of the rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1970;52B-3:540-553.

Shoulder pain: rotator cuff tears. Magnetic Resonance Update (Santa Cruz, CA: Dominican MRI Center) 1989.

Tibone JE, Jobe FW, Kerlan RK, et. al.: Shoulder impingement syndrome in athletes treated by anterior acromioplasty. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1985;198:134-140.

Shoulder Pain From Nerve Entrapment (i.e. Carpal or Cubital Tunnel Syndrome)

Crymble, B. “Brachial Neuralgia and the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” British Journal of Medicine, Vol. 3, 470-451, 1968.

Kummel BM, Zazanis GA: Shoulder pain as a presenting complaint in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1973;92:227-230.

LaBan, Myron M., Zemenick, GA, and Meerschaert, JR. “Neck and Shoulder Pain: Presenting Symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” Michigan Medicine, September 1975, pages 449-450.