Shoulder Impingement Syndrome Treatment in Nebraska

Struggling with shoulder pain? Impingement syndrome might be the culprit. This common cause of shoulder pain occurs when the rotator cuff muscles or biceps tendon rub against the acromion, often leading to weakness, discomfort during overhead activities, and difficulty lifting objects. Accurate diagnosis is vital to address soft tissue damage and relieve painful symptoms effectively.

At Nebraska Hand & Shoulder Institute P.C., we specialize in diagnosing and treating shoulder pain with advanced orthopaedic care, including impingement syndrome treatment and surgery. Our personalized approach is designed to help you move past shoulder pain and get back to enjoying life.

Don’t let shoulder pain hold you back. Schedule an appointment today for expert orthopaedic care and take the first step toward lasting relief.

Understanding Impingement Syndrome

Shoulder pain is one of the most common reasons individuals consult an orthopedist. Aside from recurrent dislocation, most shoulder issues tend to arise after the age of 30. It is crucial to distinguish pain originating from the shoulder itself from pain that may be referred from other sources, such as degenerative intervertebral discs in the neck, heart attacks, or carpal tunnel syndrome.

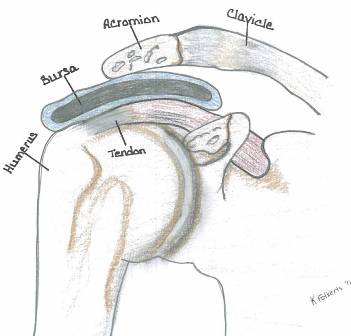

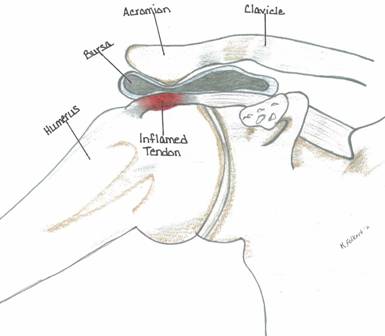

Impingement syndrome specifically refers to pain caused by the rubbing of the rotator cuff tendon and/or biceps tendon against the overlying acromion.

Normal Acromion

Prominent Acromion

Normal Acromion (Type 1)

Prominent Type 3 Acromion

Shoulder Impingement and Acromion Types

Shoulder impingement syndrome often develops when the acromion, a bony part of the shoulder blade, puts pressure on the rotator cuff tendons. This narrowing of the space can lead to pain, inflammation, and limited shoulder mobility—especially in individuals with certain acromion shapes or postural issues.

Acromion Shapes and Their Role in Shoulder Pain

There are three common types of acromion shapes, each with different implications for shoulder health:

- Type I (Flat) – Least likely to cause impingement. People with a flat acromion rarely develop shoulder pain related to this structure.

- Type II (Curved) – More likely to press against the rotator cuff.

- Type III (Hooked) – Most associated with chronic impingement and rotator cuff injuries.

Individuals with Type II or Type III acromions are much more prone to shoulder impingement and may eventually require orthopaedic evaluation if symptoms persist.

How Aging Affects the Acromion and Shoulder Joint

As we age, bone changes around the shoulder can increase the risk of impingement. One common change is acromial spur formation, especially where the acromion connects to the coracoacromial ligament. Over time, the acromion may extend downward and inward, reducing space for the rotator cuff to move freely.

Additionally, arthritis in the acromioclavicular (AC) joint often begins around age 40 or later. While many people are asymptomatic, arthritis can lead to joint enlargement, which may be felt as a bump at the top of the shoulder. This same bony overgrowth also projects downward, further crowding the rotator cuff.

The Link Between Posture and Shoulder Impingement

In some cases, poor posture can make shoulder impingement worse. Slouched or forward-rounded shoulders alter the position of the scapula (shoulder blade), which may cause the acromion to sit closer to the rotator cuff tendons.

This condition—called scapular dyskinesis—involves abnormal movement of the shoulder blades and was popularized by orthopaedic expert Dr. Ben Kibler. It is often seen in individuals whose shoulder blades are positioned too far apart in the back, leading to mechanical compression of the rotator cuff during arm movement.

Correcting posture by keeping the shoulders back and the head upright can reduce stress on the shoulder joint and improve symptoms over time.

Understanding Shoulder Anatomy and Its Role in Shoulder Pain

The shoulder joint is one of the most complex and mobile joints in the human body. Its wide range of motion allows for lifting, reaching, and rotating—but this flexibility also makes it vulnerable to shoulder pain, instability, and impingement.

The Key Joints of the Shoulder

The shoulder is made up of three important components:

- Glenohumeral Joint – This is the main ball-and-socket joint where the upper arm bone (humerus) meets the shoulder blade (scapula). It provides most of the shoulder’s movement.

- Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint – Located where the clavicle (collarbone) meets the acromion (part of the scapula), this joint helps with overhead and rotational movement.

- Scapulothoracic Articulation – While not a true joint, this is where the shoulder blade glides over the ribcage. It's essential for full arm motion and shoulder stability.

Together, these joints create a dynamic system that relies on precise coordination to move smoothly.

The Rotator Cuff: Stabilizing the Shoulder

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles that play a vital role in shoulder stability and function:

- Supraspinatus

- Infraspinatus

- Teres Minor

- Subscapularis

These muscles work together to keep the head of the humerus centered in the socket during movement. They also allow for key motions like lifting the arm, rotating the shoulder, and holding it steady during activity.

When these muscles become weak, tight, or imbalanced, it can lead to shoulder impingement syndrome, where soft tissues like tendons are pinched between bones. This is a common cause of shoulder pain without a clear injury.

Why Shoulder Anatomy Matters in Non-Traumatic Pain

Many cases of chronic shoulder pain aren't due to accidents or injuries—they’re caused by variations in shoulder anatomy or muscle imbalances. Differences in bone shape (like the acromion) or joint alignment can contribute to shoulder impingement, rotator cuff strain, and joint irritation.

Understanding this complex anatomy helps explain why some people develop pain from repetitive motion, poor posture, or aging—even without any specific injury event.

Causes and Symptoms of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome

Shoulder impingement syndrome is one of the most common causes of shoulder pain, especially in adults over the age of 30. It occurs when the soft tissues of the shoulder—particularly the rotator cuff tendons and subacromial bursa—become pinched or compressed by surrounding bone and ligaments during arm movement.

This condition can be caused by several factors, including age-related changes, joint instability, and anatomical variations.

Common Causes of Shoulder Impingement

1. Age-Related Bone Changes

As we age, the shape of the shoulder bones can change—especially the acromion, the bony top part of the shoulder blade. Over time, the front edge of the acromion may elongate and thicken, particularly as the coracoacromial (CA) ligament calcifies. These changes reduce the space for the rotator cuff tendons and increase the risk of impingement. That’s why shoulder impingement syndrome is more frequently diagnosed in adults over 30.

2. Rotator Cuff Degeneration

The supraspinatus tendon, part of the upper rotator cuff, is often affected by wear and tear over time. This tendon sits directly beneath the acromion and is especially vulnerable to compression and inflammation. Degeneration of this tendon is a leading cause of impingement-related shoulder pain.

3. Poor Posture or Muscle Imbalance

Weak shoulder muscles, muscle fatigue, or poor scapular control can cause the shoulder to shift into a position that increases pressure on the rotator cuff and bursa. This is known as dynamic instability, where the muscles fail to keep the shoulder joint properly aligned during movement.

This form of impingement is often seen in overhead athletes or individuals with hypermobile (overly flexible) joints, such as baseball pitchers or swimmers.

4. Structural or Functional Instability

Some individuals experience functional instability, where the muscles and ligaments don’t work well together to support the shoulder. While structural abnormalities may not always be visible, the result is the same—reduced space for soft tissues, leading to impingement.

5. Overlapping Conditions

Many people with impingement also deal with coexisting issues, such as arthritis in the cervical spine, pinched nerves, or degenerative changes in other parts of the shoulder. These overlapping problems can make diagnosis and treatment more complex.

Symptoms of Shoulder Impingement

Common signs and symptoms of impingement syndrome include:

- Pain when lying down, especially on the affected side

- Pain during shoulder motion between 60° and 120°, especially when lifting or reaching overhead

- Weakness or discomfort when lifting objects

- Limited range of motion and shoulder stiffness

- Pain that may improve temporarily with rest or activity modification

Symptoms of Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Arthritis

In some cases, shoulder pain is due to AC joint arthritis, which can overlap with impingement. Signs include:

- Pain at the top of the shoulder

- Discomfort during arm movement from 120° to 180° of abduction

- A visible or palpable bump over the AC joint in more advanced stages

What the Doctor Looks For During the Exam

During a physical examination, an orthopaedic specialist may note:

- Reduced shoulder mobility

- Localized tenderness around the acromion or rotator cuff

- Guarding behavior or hesitation when actively moving the arm

- Pain relief after injecting a local anesthetic into the shoulder (diagnostic and therapeutic)

How Shoulder Impingement Is Diagnosed

Accurate diagnosis requires a combination of patient history, physical examination, and imaging tests.

X-Rays

Standard shoulder X-rays help evaluate:

- Acromion shape

- Bone spurs (osteophytes)

- Joint space narrowing

- Signs of arthritis or sclerosis

- Calcification of tendons or ligaments

Arthrogram

If conservative treatments don’t relieve symptoms, an arthrogram may be recommended. This involves injecting a contrast dye into the shoulder joint to assess whether there is a leak from the joint capsule, which could indicate a tear or joint irregularity.

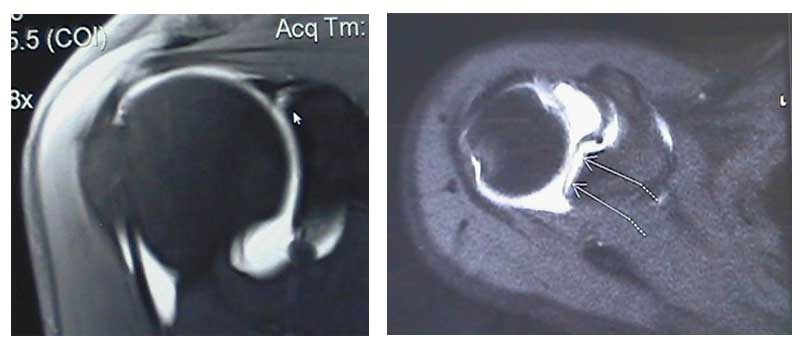

MRI Scans

While MRI scans are commonly used, they can sometimes be less effective than arthrograms in detecting subtle differences between rotator cuff inflammation vs. tears. MRIs are typically more expensive and are generally reserved for complex or recurrent cases.

Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: Treatment Options and Surgical Approaches

Treatment for shoulder impingement depends on the severity of symptoms, the degree of tissue involvement, and how well a patient responds to conservative care. Below are both non-surgical and surgical approaches commonly used to manage and resolve symptoms.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Corticosteroid Injections

For moderate to severe shoulder pain with restricted motion, a corticosteroid injection into the subacromial space can provide rapid relief. The goal is to reduce inflammation around the rotator cuff tendons and bursa, often resulting in immediate improvement.

- Injections may be repeated if symptoms persist over several weeks.

- Often paired with oral NSAIDs, this approach is effective in about 70% of cases.

- Physical therapy is typically recommended to improve shoulder mechanics and prevent recurrence.

Arthroscopic Acromioplasty

If pain continues despite conservative care—especially if it affects sleep, work, or daily activity—minimally invasive impingement syndrome surgery may be recommended.

What It Involves:

- A fiberoptic scope is inserted through small incisions to access the joint.

- The surgeon removes bone spurs and reshapes the underside of the acromion to decompress the rotator cuff.

- In up to 40% of cases, the AC joint is also trimmed to relieve arthritis-related pain.

This procedure, known as acromioplasty, is typically performed on an outpatient basis.

Recovery:

- Many patients return to light activity within a week.

- Full range of motion and pain resolution is often achieved in 3 to 6 months.

- Strict activity restrictions are generally not required after surgery.

Rotator Cuff Tear Repair

If imaging or arthroscopy reveals a rotator cuff tear, surgical repair may be necessary.

Procedure Highlights:

- The torn or degenerated portion of the tendon is removed.

- The remaining tendon is reattached to the bone using sutures or anchors.

- Patients must avoid lifting the arm overhead or to the side for 4 to 6 weeks post-op.

- Heavy lifting is avoided for up to 3 months to ensure proper healing.

Managing Labral Tears

Labral tears—especially in the presence of impingement—may also require surgical attention.

Treatment Considerations:

- Labral tears are often trimmed or anchored during shoulder arthroscopy.

- In patients over age 40, labral repair is less predictable and may lead to stiffness.

- Instead, many surgeons now perform a biceps tenodesis, where the biceps tendon is detached from the labrum and reattached to the upper humerus. This relieves labral tension and improves outcomes.

Biceps Tenodesis vs. Tenotomy:

- Tenodesis preserves strength and minimizes post-op complications.

- Tenotomy is a quicker procedure but may cause up to 20% strength loss, visible muscle deformity ("Popeye sign"), and ongoing shoulder aching in some patients.

- Tenodesis is generally preferred, especially for active individuals or those with high functional demands.

Expert Perspective

Dr. Ichtertz supports a stepwise treatment approach—starting with conservative care and progressing to shoulder impingement syndrome surgery only when necessary. In surgical cases, techniques like arthroscopic decompression, rotator cuff repair, and biceps tenodesis offer long-term relief with reliable outcomes, especially when tailored to the patient's anatomy and activity level.

Above are MRI images of labral tears. The arrows in each image are pointing to where the dye has leaked into the labral tear.

WARNING: MAY CONTAIN GRAPHIC IMAGES

Preventing Frozen Shoulder During Recovery

One of the most important aspects of recovery is maintaining shoulder mobility to avoid frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis). This condition occurs when the joint capsule tightens and restricts movement, leading to prolonged stiffness and pain.

- Gentle range of motion exercises are essential and may be guided by a physical therapist.

- Treatments may include passive and assisted movement, hot or cold therapy, and home exercises.

- Severe cases may require manipulation under anesthesia, so early intervention is key.

- Stay as active as your treatment allows to prevent complications from joint stiffness.

Calcific Tendonitis

Calcific tendonitis is caused by calcium deposits within the rotator cuff tendons, usually the supraspinatus. Though it may mimic impingement symptoms, it is a separate condition.

- A corticosteroid injection directly into the area typically brings fast relief.

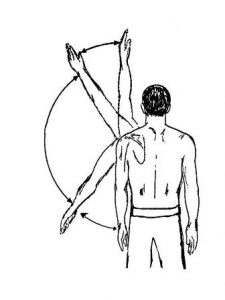

- While healing, avoid overhead reaching, throwing, and circular arm movements that can worsen inflammation.

- This condition is generally not associated with rotator cuff tears, and recovery is often complete with conservative care.

Post-Op Synopsis for Impingement (Rotator Cuff Intact)

Recovery after arthroscopic acromioplasty or shoulder impingement surgery (without a cuff tear) is generally smooth. Here’s what to expect:

- Day 3: Return to light activity or work as tolerated.

- Weeks 2–3: Begin physical therapy if full range of motion hasn't returned.

- Months 3–6: Anticipate full or near-full recovery with proper rehab and follow-up.

Returning to Sports After Shoulder Treatment

Getting back into athletic activity should be gradual. Start with mobility-focused exercises and ease into intensity.

Tips by Sport Type:

- Tennis & Overhead Sports: Limit overhead swings initially; build back up over time.

- Swimming: Backstroke, breaststroke, and sidestroke are generally better tolerated than butterfly or crawl.

- Throwing Sports: Start with light throws, gradually increasing force while maintaining proper mechanics.

Surgical Results and Long-Term Outlook

Surgical treatment for shoulder impingement or rotator cuff issues offers excellent results for most patients. Studies show:

- 85% of individuals experience significant pain relief and improved mobility after surgery.

- Outcomes are influenced by age, physical activity level, and presence of other conditions (e.g., cervical spine issues).

- Timing matters: For rotator cuff tears, outcomes are best when repaired within 3 weeks of injury.

- Treating impingement early may also prevent tendon tears from developing later on.

Take the Next Step Toward Shoulder Relief

If you’re struggling with ongoing shoulder pain, limited motion, or symptoms of impingement, early treatment can make all the difference. Whether you need conservative care, diagnostic clarity, or expert surgical intervention, our team is here to help.

Contact us today to schedule a consultation and explore the best treatment options for your shoulder health. Let’s get you back to doing what you love—without pain.

Bigliani LH, Morrison DS, April EW: The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Ortho Transactions, 1986;10:228.

Burkhead Jr, WZ: The Biceps Tendon. (Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1990. The Shoulder, Chpt 20, pp. 791-836).

Calvert PT, et. al.: Arthrography of the shoulder after operative repair of the torn rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1986;68B 1:147-150.

Crymble, B. “Brachial Neuralgia and the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” British Journal of Medicine, Vol. 3, 470-451, 1968.

Edelson JG, Taitz C: Anatomy of the coraco-acromial arch; relation to degeneration of the acromion. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1992;74B-4:589-594.

Edelson JG: The ‘hooked’ acromion revisited. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1955;77B-2:284-287.

Gartsman G: Arthroscopic acromioplasty for lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1990;72A-2:169-180

Ha’eri G, et. al.: Shoulder impingement syndrome: results of operative release. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1982;168:128-132.

Kummel BM, Zazanis GA: Shoulder pain as a presenting complaint in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1973;92:227-230.

LaBan, Myron M., Zemenick, GA, and Meerschaert, JR. “Neck and Shoulder Pain: Presenting Symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” Michigan Medicine, September 1975, pages 449-450.

Matsen FA III, Harntz C: Subacromial impingement. (Philadelphia, PA: Saunders 1990. The Shoulder, Chpt 15, pp. 623-246).

MRI of rotator cuff tears. MR Insights (Orange, CA: Alliance Imaging, Inc.), Vol. 4, No. 3, Fall 1994.

Neer CS II: Impingement lesions. Clinical Ortho & Related Research,1983;173:70-77.

Neer CS II: Anterior acromioplasty for chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1972;54A:41.

Nirschl RP: Rotator cuff tendonitis: basic concepts of pathoetiology. AAOS Instructional Course Lect., 1989;38:439-445.

Post M, Cohen J: Imipingement syndrome: a review of late stage II and early stage III lesions. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1986;207:126-132.

Rathbun JB, Macnab I: The microvascular pattern of the rotator cuff. J Bone & Joint Surg, 1970;52B-3:540-553.

Shoulder pain: rotator cuff tears. Magnetic Resonance Update (Santa Cruz, CA: Dominican MRI Center) 1989.

Tibone JE, Jobe FW, Kerlan RK, et. al.: Shoulder impingement syndrome in athletes treated by anterior acromioplasty. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1985;198:134-140.

Shoulder Pain From Nerve Entrapment (i.e. Carpal or Cubital Tunnel Syndrome)

Crymble, B. “Brachial Neuralgia and the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” British Journal of Medicine, Vol. 3, 470-451, 1968.

Kummel BM, Zazanis GA: Shoulder pain as a presenting complaint in carpal tunnel syndrome. Clinical Ortho & Related Research, 1973;92:227-230.

LaBan, Myron M., Zemenick, GA, and Meerschaert, JR. “Neck and Shoulder Pain: Presenting Symptoms of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome.” Michigan Medicine, September 1975, pages 449-450.